A Technical Deep Dive into Efficient Recipe Generation with Qwen2.5-1.5B

Large language models are impressive generalists—they can write poetry, explain quantum physics, and debate philosophy. But ask them to write a proper recipe, and things get... interesting. They'll confidently instruct you to "sauté the flour" or "bake at room temperature for 45 minutes."

This publication documents my journey to fix that. Using QLoRA (Quantized Low-Rank Adaptation), I transformed Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct from a well-meaning but culinarily confused assistant into a genuine recipe specialist. The results? A 59% improvement in ROUGE-1, an eyebrow-raising 299% improvement in ROUGE-2, and—crucially—97% retention of general language capabilities. The model didn't forget how to think; it just learned how to cook.

All code, evaluation results, and model weights are publicly available. This isn't just a paper—it's a reproducible blueprint for anyone who wants to teach their own model a new trick.

The modern kitchen, it turns out, is not so different from a machine learning laboratory. Both require precise measurements, careful attention to timing, and the humbling acceptance that not every experiment will produce edible results.

Yet while human chefs spend years perfecting their craft through apprenticeship and practice, I found myself wondering: could a language model learn to cook in under a few hours?

This question, frivolous as it may sound, touches on one of the most practical challenges in applied NLP: domain adaptation. Pre-trained language models arrive with encyclopedic knowledge absorbed from vast internet corpora, but this knowledge is necessarily shallow across specialized domains. A model might know that recipes exist. It might even generate plausible-sounding culinary instructions. But it rarely captures the structural conventions, ingredient relationships, and procedural logic that distinguish a usable recipe from a confidently hallucinated disaster.

The challenge of domain adaptation: teaching general knowledge models to excel in specialized tasks.

One evening, sitting in my cozy bedroom, a deceptively simple question crossed my mind:

Can I efficiently fine-tune a compact language model to excel at domain-specific text generation while minimizing catastrophic forgetting of general language understanding capabilities?

The emphasis on "efficiently" is deliberate. I specifically avoided the computationally extravagant approach of full fine-tuning—the kind that requires a small power plant and a second mortgage. Instead, I wanted to explore whether parameter-efficient methods could achieve comparable results while remaining accessible to practitioners without enterprise-scale resources.

Spoiler: they can. But the journey to prove it? That's where things got interesting.

Of all possible domains, why did I choose recipes? Beyond my personal appreciation for food that doesn't come from a microwave, recipe generation offers several characteristics that make it an ideal testbed:

Structural Rigidity: Recipes follow predictable formats—title, ingredients, directions—allowing clear evaluation of format adherence. No points for creativity when the instructions are incomprehensible.

Domain Vocabulary: Culinary terminology ("julienne," "braise," "fold") requires specific knowledge unlikely to appear prominently in general web text. Your average Reddit thread doesn't casually drop "deglaze the fond."

Procedural Logic: Steps must follow sensible sequences. You cannot "let cool" before heating, nor "serve" before cooking. Unless you're into culinary avant-garde performance art.

Objective Evaluation: Unlike creative writing, recipes can be compared against reference texts using established metrics. No arguing about whether the recipe "spoke to your soul."

Practical Utility: Millions of users interact with recipe systems daily. This isn't an academic exercise—it's genuinely useful.

This work delivers the following:

But before we dive into the how, let's talk about the tools that made this possible.

If you're already familiar with LoRA and QLoRA, feel free to skip ahead to Section 3. But if you've ever wondered how we can fine-tune billion-parameter models without melting our GPUs, stick around—the magic is actually quite elegant.

Here's a counterintuitive insight that changed everything: when you fine-tune a model, you don't actually need to update all the weights.

The core idea behind LoRA (Low-Rank Adaptation) is that the changes needed for task adaptation live in a much smaller subspace than the full parameter space. Instead of modifying billions of weights, you add small trainable matrices alongside the frozen original weights. These adapters learn the task-specific adjustments while the base model stays untouched.

The result? I went from needing to train billions of parameters to training just a few million. That's not a typo—it's roughly a 99.5% reduction in trainable parameters.

LoRA was already impressive, but QLoRA takes it further by adding quantization to the mix. The base model gets compressed to 4-bit precision (yes, four bits per parameter), which means I can load and fine-tune models that would otherwise trigger an out-of-memory error and send my GPU into an existential crisis.

The model stays compressed during training while the LoRA adapters operate in higher precision. It's like having your cake and eating it too—except the cake is model performance and the eating is memory efficiency.

I chose Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct as my base model. The "Instruct" suffix is crucial—this model already knows how to follow instructions and hold conversations. It understands chat formats, can parse user requests, and generates coherent responses.

Why does this matter? Because I don't need to teach it how to communicate. I just need to teach it what to say when the topic is cooking. It's the difference between teaching someone a new language versus teaching a fluent speaker new vocabulary.

There's a catch with fine-tuning that every practitioner learns the hard way: models tend to forget what they knew before. Train too aggressively on recipes, and suddenly your model thinks the capital of France is "preheat oven to 350°F."

This phenomenon—catastrophic forgetting—is the specter haunting every fine-tuning endeavor. LoRA provides natural protection since most original weights stay frozen, but "natural protection" isn't the same as "guaranteed immunity."

I needed to verify this through careful benchmarking. (Spoiler alert: the model retained 97% of its general capabilities. The kitchen didn't destroy the library.)

Now that we have our tools, let's see how I put them to work.

My methodology follows a systematic pipeline: dataset selection, base model evaluation, QLoRA fine-tuning, and comprehensive evaluation. Each phase informed subsequent decisions, creating an iterative refinement loop. Think of it as the scientific method, but with more YAML files.

I utilized the recipe-nlg-llama2 dataset from Hugging Face, containing approximately two million recipes. Two. Million. That's roughly the population of Paris, except instead of people, it's instructions for making dinner.

The dataset includes structured fields:

| Field | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

title | Recipe name | "Honey Garlic Chicken" |

NER | Named entities (ingredients) | "chicken, garlic, honey, soy sauce" |

ingredients | Full ingredient list | "2 lbs chicken thighs, 4 cloves garlic..." |

directions | Cooking instructions | "1. Preheat oven to 375°F..." |

The NER field proved particularly valuable—it provides a condensed ingredient list perfect for prompting the model without overwhelming the context window.

Data Splits:

Yes, the validation and test sets are small. This was deliberate—balancing statistical significance against the very real cost of running inference during iterative experimentation. When you're debugging at 2 AM, you want fast feedback loops.

Before committing computational resources to fine-tuning, I needed to find the right starting point. I auditioned four candidates:

| Model | Parameters | Type | System Message |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLaMA 3.2-1B-Instruct | 1B | Open-source | Supported |

| Gemma 2-2B-IT | 2B | Open-source | Not supported |

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B-Instruct | 1.5B | Open-source | Supported |

| GPT-4o-mini | Unknown | Commercial | Supported |

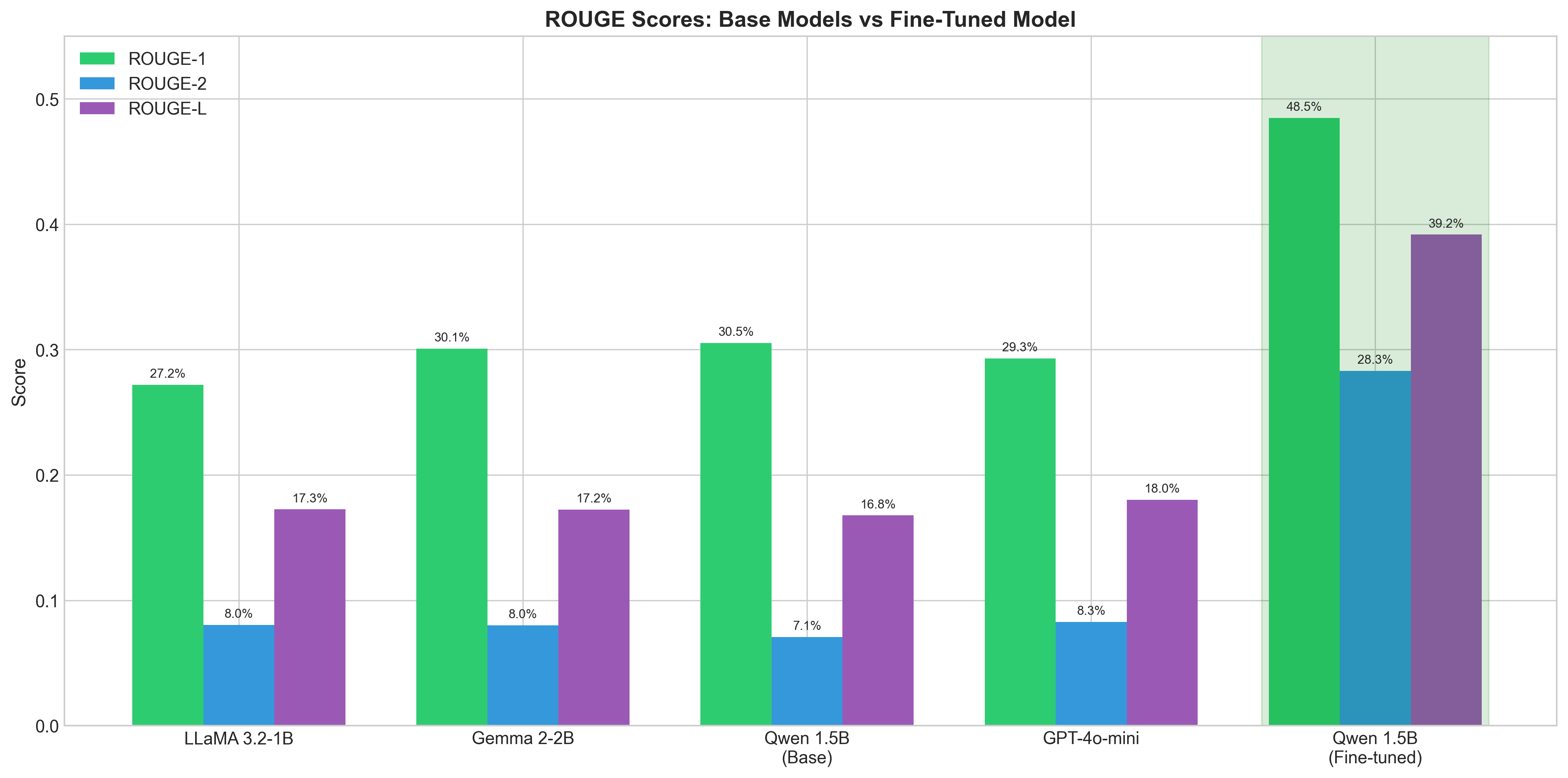

Each model received identical prompts requesting recipe generation based on provided ingredients. I computed ROUGE scores against ground-truth recipes:

ROUGE score comparison across base models. The race was tighter than I expected.

Baseline Results:

| Model | ROUGE-1 | ROUGE-2 | ROUGE-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| LLaMA 3.2-1B-Instruct | 27.2% | 8.0% | 17.3% |

| Gemma 2-2B-IT | 30.1% | 8.0% | 17.2% |

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B-Instruct | 30.5% | 7.1% | 16.8% |

| GPT-4o-mini | 29.3% | 8.3% | 18.0% |

Interesting. None of them were great at recipes out of the box. But one stood out—and not just because of ROUGE-1.

I selected Qwen 2.5-1.5B-Instruct based on a combination of factors:

Highest ROUGE-1 (30.5%): Qwen demonstrated superior unigram overlap with reference recipes, suggesting better coverage of ingredients and cooking verbs.

Native System Message Support: Unlike Gemma, Qwen supports dedicated system messages. This enables cleaner prompt engineering without hacky concatenation workarounds.

Optimal Size: At 1.5B parameters, Qwen sits in a productive sweet spot—large enough for meaningful knowledge retention, small enough for efficient QLoRA training on consumer GPUs.

Quantization Compatibility: Qwen works seamlessly with 4-bit NF4 quantization via bitsandbytes. No architectural surgery required.

The observant reader may note that GPT-4o-mini achieved the highest ROUGE-L and ROUGE-2 scores. But commercial API models can't be fine-tuned by practitioners like us—they're a ceiling we can admire but not modify. The goal was to create something we control.

With our champion selected, it was time for training.

My QLoRA configuration balances adaptation capacity against training stability:

# Quantization Settings load_in_4bit: true bnb_4bit_quant_type: nf4 bnb_4bit_use_double_quant: true bnb_4bit_compute_dtype: bfloat16 # LoRA Architecture lora_r: 16 # Rank of adaptation matrices lora_alpha: 32 # Scaling factor (alpha/r = 2) lora_dropout: 0.1 # Regularization target_modules: ["q_proj", "v_proj"] # Attention projections only

The choice of lora_r=16 represents a deliberate trade-off. Higher ranks increase adaptation capacity but also training cost and overfitting risk. My preliminary experiments showed diminishing returns beyond rank 16 for this dataset—more capacity doesn't help when you've already captured the pattern.

Targeting only query and value projections (q_proj, v_proj) follows established practice. Including key projections or MLP layers might yield marginal improvements, but the cost-benefit ratio wasn't compelling.

# Training Hyperparameters num_epochs: 1 max_steps: 300 learning_rate: 2e-4 batch_size: 4 gradient_accumulation_steps: 4 sequence_len: 512 lr_scheduler: cosine warmup_steps: 50 optimizer: paged_adamw_8bit

The effective batch size of 16 (4 × 4 accumulation steps) provided stable gradient estimates while fitting within GPU memory constraints. The cosine learning rate schedule with 50 warmup steps prevented early training instability—important when you're updating so few parameters that every gradient matters.

Here's an implementation detail that's easy to overlook but critical to get right: assistant-only masking.

During training, I compute loss only on tokens corresponding to the model's response, ignoring the instruction portion:

# Mask prompt tokens, train only on assistant response labels = [-100] * prompt_length + tokens["input_ids"][prompt_length:]

Why does this matter? Without masking, the model wastes capacity learning to predict the prompt—tokens it will never need to generate. With masking, every gradient signal focuses on what we actually care about: generating good recipes.

It's the difference between a student studying the exam questions versus studying the answers.

Training was conducted on RunPod cloud GPU infrastructure:

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| GPU | NVIDIA A100 (40GB) |

| Training Time | ~1 hour for 300 steps |

| Peak Memory | ~12GB with 4-bit quantization |

| Multi-GPU Support | DDP (1-8 GPUs) |

One hour. That's it. The time it takes to watch two episodes of a cooking show is all the compute needed for meaningful domain adaptation. QLoRA's practical appeal lies precisely here: you don't need a data center to teach a model new tricks.

But did any of this actually work? Time to find out.

Evaluation of generative models is notoriously tricky. A single metric cannot capture the multidimensional nature of text quality—it's like rating a restaurant based solely on portion size. So I adopted a three-pronged strategy: check whether the recipes look right (ROUGE), check whether they mean the right things (BERTScore), and verify the model didn't forget everything else (benchmarks).

ROUGE (Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation) measures n-gram overlap between generated and reference texts:

These metrics are imperfect (you could score well by repeating "chicken" 50 times), but they provide interpretable signals about vocabulary usage and phrase construction.

BERTScore computes semantic similarity using contextual embeddings. This catches what ROUGE might miss: a model could use synonymous terms and produce semantically equivalent recipes that score poorly on lexical metrics but well on semantic ones.

Think of it as the difference between matching words versus matching meaning.

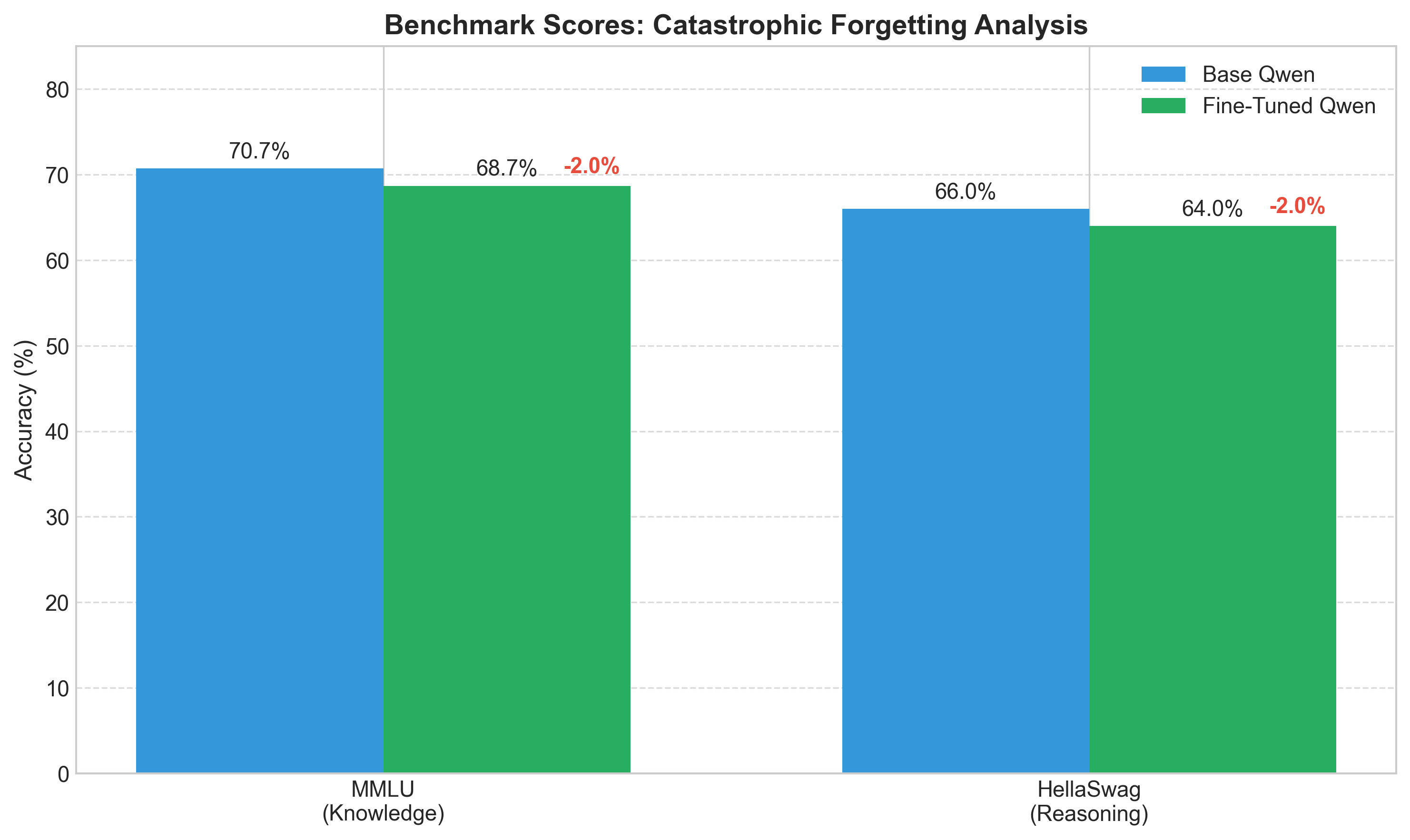

To verify that fine-tuning didn't lobotomize the model's general capabilities, I evaluated on:

Significant drops on these benchmarks would indicate problematic forgetting—a Pyrrhic victory where we gained recipes but lost the ability to reason.

The evaluation framework was ready. The model had trained. Time for the moment of truth.

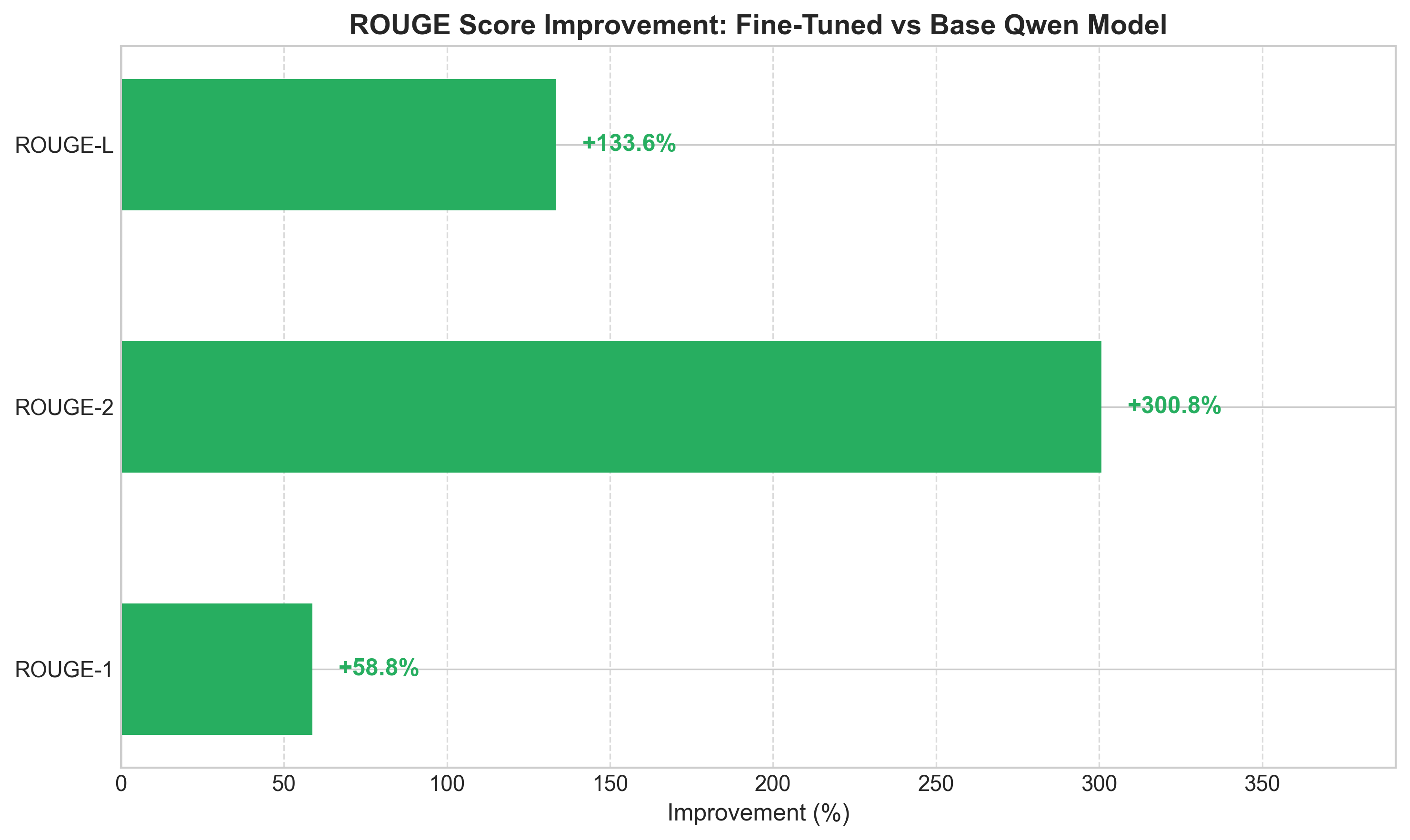

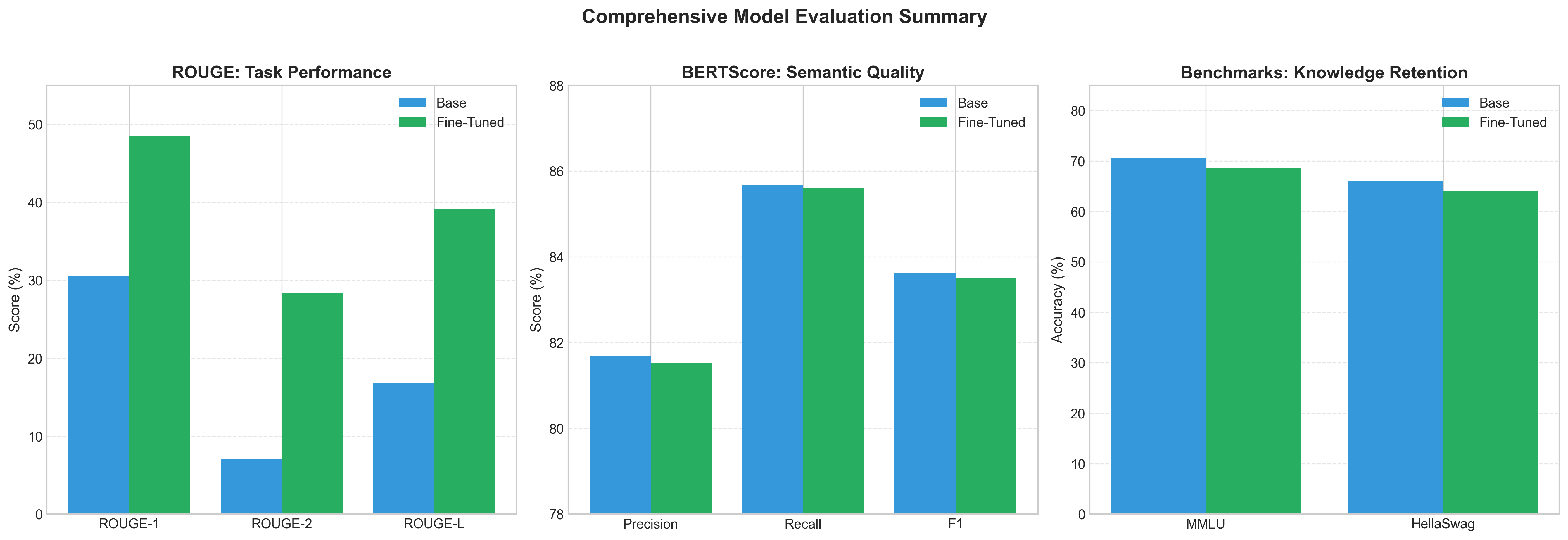

The fine-tuned model achieved dramatic improvements across all ROUGE metrics:

| Model | ROUGE-1 | ROUGE-2 | ROUGE-L |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B (Base) | 30.5% | 7.1% | 16.8% |

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B (Fine-tuned) | 48.5% | 28.3% | 39.2% |

Relative Improvements:

ROUGE score improvements after QLoRA fine-tuning. That ROUGE-2 bar? It's not a typo.

Let me dwell on that ROUGE-2 number for a moment: 299% improvement. Nearly four times better at generating the right word pairs.

Why such a dramatic jump? ROUGE-2 captures bigram overlap—phrases like "preheat oven," "medium heat," "stir constantly," "let cool." These are the bread and butter (pun intended) of recipe writing, appearing thousands of times across two million training examples. The base model, trained on diverse web content, rarely encountered these patterns in high concentration. Fine-tuning changed that dramatically.

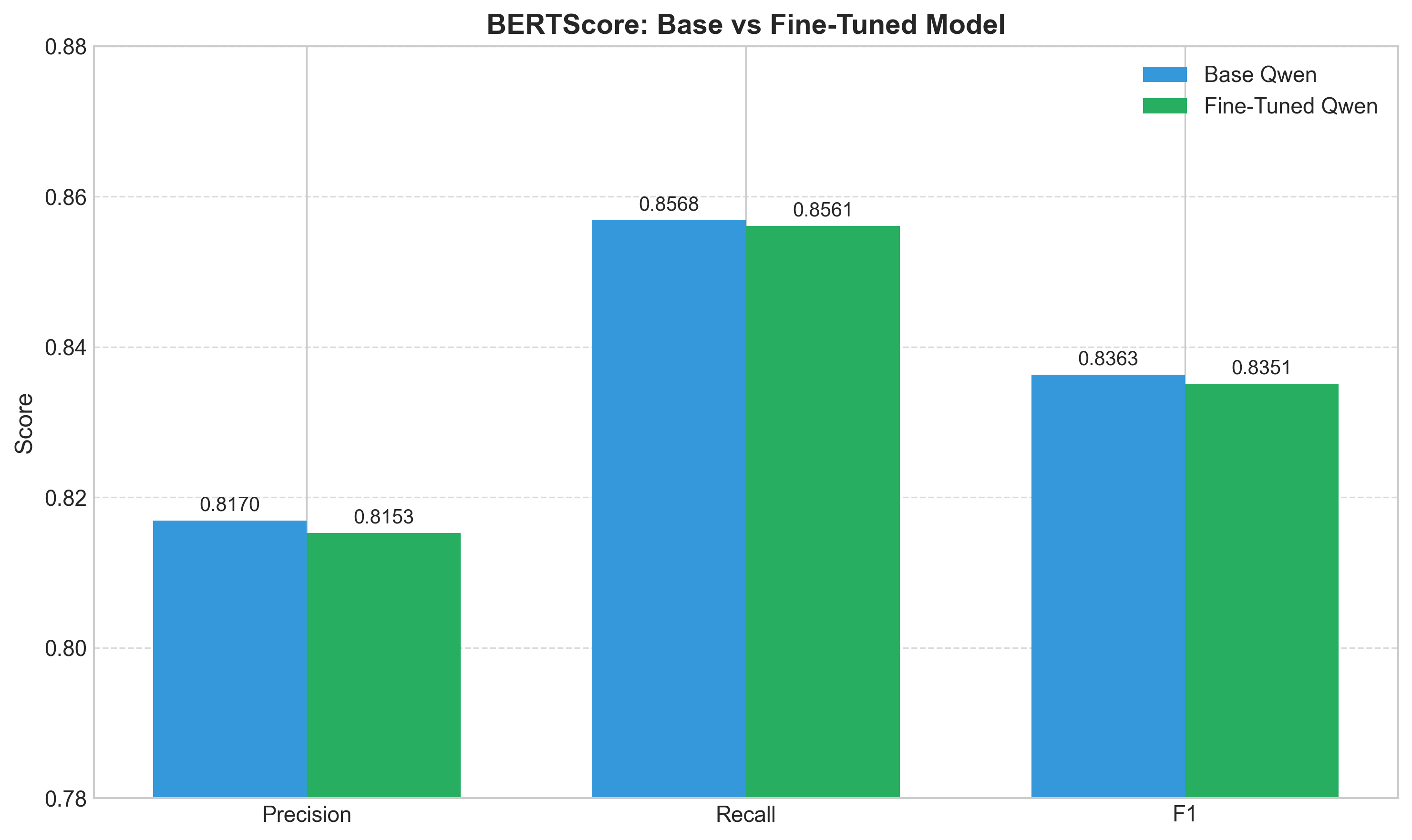

But here's where it gets interesting. Did the model actually understand recipes better, or just learn to parrot common phrases?

| Model | Precision | Recall | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B (Base) | 0.817 | 0.857 | 0.836 |

| Qwen 2.5-1.5B (Fine-tuned) | 0.815 | 0.856 | 0.835 |

| Change | -0.002 | -0.001 | -0.001 |

BERTScore comparison. Virtually identical—and that's exactly what we wanted.

The negligible BERTScore change (<0.2%) reveals something crucial: the ROUGE improvements stem from format and vocabulary alignment, not semantic drift. The model learned to express culinary content using conventional recipe language without fundamentally altering what it was trying to say.

It found the right words for thoughts it could already think.

Now for the moment I was dreading. Did teaching the model to cook make it forget how to think?

| Benchmark | Base Model | Fine-Tuned | Change | Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MMLU | 70.7% | 68.7% | -2.0% | 97.2% |

| HellaSwag | 66.0% | 64.0% | -2.0% | 97.0% |

General capability benchmarks. The model remembered almost everything.

A consistent 2% degradation across both benchmarks—detectable, but minor. The model retained 97% of its general capabilities while achieving 59-299% improvements in task performance.

This is the best-case scenario for domain adaptation: the model didn't sacrifice its general knowledge to become a culinary specialist. It became a generalist who happens to excel at recipes. Like a polymath who picked up cooking during a sabbatical.

The comprehensive view: massive task gains, preserved semantics, minimal forgetting.

The numbers tell a compelling story, but numbers alone don't capture what it feels like to use the model. For that, we need examples.

Abstract metrics are encouraging, but they can't substitute for actually seeing what the model produces. Let's look at some real outputs.

Input Ingredients: chicken breast, marinara sauce, penne noodles, Merlot wine, olive oil, water, cilantro

Generated Recipe:

Chicken Penne

Ingredients:

- chicken breast

- marinara sauce

- penne noodles

- Merlot wine

- olive oil

- water

- cilantro

Directions:

- Preheat oven to 375 degrees F (190 degrees C). Place the chicken breasts in a large baking dish; brush with olive oil and sprinkle with salt and pepper. Bake until cooked through, about 20 minutes. Remove from oven and let cool slightly.

- Meanwhile, cook the pasta according to package directions. Drain well.

- In a small bowl, whisk together the marinara sauce, wine, and water. Pour over the chicken and toss to coat. Add the pasta and toss to combine. Sprinkle with cilantro leaves and serve hot.

Notice what the model does right: proper structure (title, ingredients, numbered directions), appropriate culinary terminology ("brush with olive oil," "toss to coat"), and a coherent procedural sequence. The wine gets incorporated into the sauce, the pasta cooks meanwhile—these aren't random instructions.

Input Ingredients: olive oil, potatoes, onion, eggs, salt, pepper, flat-leaf parsley

Generated Recipe:

Potato Frittata

Ingredients:

- olive oil

- potatoes

- onion

- eggs

- salt

- pepper

- flat-leaf parsley

Directions:

- Heat the oil in a large skillet over medium heat; add the potatoes and cook until tender, about 10 minutes.

- Add the onion and cook until soft, about 5 minutes.

- Remove from heat and let cool slightly.

- In a bowl, whisk together the eggs, salt, and pepper.

- Stir in the cooled potato mixture.

- Pour into a greased 9-inch baking dish.

- Bake at 375°F (180°C) for 20 to 25 minutes or until set.

Here's what impressed me: the model demonstrates procedural understanding. Potatoes are cooked before eggs are added (correct—you can't cook raw potatoes in a frittata). The potato mixture is cooled before combining with eggs (correct—hot potatoes would scramble the eggs prematurely). The baking temperature is reasonable for egg dishes.

These aren't just word patterns. The model learned something about how cooking works.

For practitioners seeking to reproduce or extend this work, I've provided a complete, modular codebase. Everything you need is organized and documented.

Qwen-QLoRA-Chef/

├── code/

│ ├── train_qlora.py # Single-GPU training

│ ├── train_qlora_ddp.py # Multi-GPU distributed training

│ ├── evaluate_qlora_Rouge.py # ROUGE evaluation

│ ├── evaluate_qlora_BERT.py # BERTScore evaluation

│ ├── config.yaml # Centralized configuration

│ └── utils/

│ ├── config_utils.py # Configuration loading

│ ├── data_utils.py # Dataset preprocessing

│ ├── model_utils.py # Model setup and quantization

│ └── inference_utils.py # Generation and metrics

├── notebooks/

│ ├── Data_Preprocessing.ipynb

│ ├── Evaluate_Baseline_Models_Rouge.ipynb

│ └── Model_Evaluation_Comparison.ipynb

├── Rouge_Scores/ # Evaluation results

├── BERT_Scores/

├── Benchmark_Scores/

└── Images_Publication/ # Visualizations

Configuration Management: All hyperparameters live in config.yaml. This enables reproducible experiments through configuration versioning—change settings, not code.

Modular Utilities: The utils/ package separates concerns cleanly. Need to tweak data loading? Edit data_utils.py. Model setup? model_utils.py. You never have to grep through a monolithic script.

Distributed Training Support: The train_qlora_ddp.py script leverages Hugging Face Accelerate for seamless scaling from single-GPU to multi-GPU training. Same code, more GPUs, faster results.

The fine-tuned model is available on Hugging Face Hub, ready to use:

Download, load, generate. It's that simple.

No project is without limitations, and intellectual honesty demands I acknowledge mine.

Evaluation Set Size: The 200-sample test set, while sufficient for comparative evaluation, may not capture rare failure modes. The model might still confidently suggest "bake the ice cream at 400°F" in edge cases I haven't tested.

English Focused: The training data and evaluation focus exclusively on English-language recipes. Whether these techniques transfer to multilingual settings remains unexplored. French cuisine might require French finesse.

Temporal Knowledge: The base model's knowledge cutoff affects its understanding of contemporary culinary trends. Don't expect cutting-edge molecular gastronomy or TikTok-viral recipes from 2024.

Several extensions beckon:

Controllable Generation: Conditioning on dietary restrictions, cuisine types, or difficulty levels would dramatically increase practical utility. Imagine: "Generate a vegan Thai recipe, intermediate difficulty."

Human Evaluation: Systematic user studies comparing generated recipes against human-authored alternatives would provide ground-truth quality assessment. Metrics are proxies; humans are the final judges.

The road ahead is clear—and I suspect others will travel it faster than I could alone. That's why everything is open source.

I set out to answer a simple question: can you efficiently teach a language model to excel at a specialized domain without breaking its general capabilities?

The answer, as demonstrated through this work, is a resounding yes.

Starting from Qwen2.5-1.5B-Instruct—a general-purpose model with no special culinary training—I produced a specialized recipe generator achieving 59% ROUGE-1 improvement while retaining 97% of general capabilities. All within approximately one hour of training on commodity cloud hardware.

The "Qwen-QLoRA-Chef" metaphor, while playful, captures something essential. Just as a chef's apprentice builds upon general kitchen knowledge to develop specialized expertise, the model built upon pre-trained language understanding to develop domain-specific generation abilities. Neither the apprentice nor the model forgot how to speak or think generally—they simply acquired new competencies layered atop existing foundations.

For practitioners, this work offers a reproducible blueprint:

The complete codebase, trained weights, and evaluation results are publicly available. Clone it, adapt it, improve it. The kitchen is open.

The kitchen, as it turns out, makes an excellent laboratory.

And the model? It learned to cook.

This work stands on the shoulders of the open-source AI community:

I'm Daniel Krasik—a data anaylst and AI enthusiast who believes that the best technical work happens when complexity meets clarity.

My passion lies at the intersection of building things that work and explaining why they work. I spend my days exploring practical applications of AI, designing real-world ML workflows, and translating dense technical concepts into insights that others can actually use. This project is a perfect example: I wanted to understand domain adaptation deeply enough to teach it, and I wanted to share that understanding in a way that saves others the rabbit holes I fell into.

When I'm not fine-tuning models or debugging training runs at unreasonable hours, you'll probably find me exploring great food. There's a reason I chose recipe generation for this project—good ideas, like good meals, are worth savoring. And honestly? The best debugging sessions happen with a proper meal waiting as motivation.

Feel free to connect, ask questions, or share what you build with this work. The best part of open source is watching ideas evolve in directions you never imagined.

Find me on:

@software{qwen_qlora_chef_2025, author = {Daniel Krasik}, title = {Qwen-QLoRA-Chef: Fine-tuning Qwen2.5 for Recipe Generation using QLoRA}, year = {2025}, publisher = {GitHub}, url = {https://github.com/Daniel-Krasik/Qwen-QLoRA-Chef}, note = {A complete pipeline for domain-adaptive language model fine-tuning} }

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). You are free to share and adapt this material for non-commercial purposes, provided appropriate attribution is given and derivative works are distributed under the same license.

"The only time to eat diet food is while you're waiting for the steak to cook." — Julia Child

"The only time to use a base model is while you're waiting for the fine-tuning to finish." — This Publication