Introduction

The interplay between the gut microbiota and the brain has emerged as a pivotal area of research, uncovering complex mechanisms that influence neurological processes through the gut-brain axis. Recent studies have highlighted the role of diet, particularly sugar consumption, in shaping microbiota composition and activity, which in turn mediates its influence on the brain. In this scenario, the role of the microbiota is crucial, as sugars exert their neurological effects mainly through the microbial populations in the gut.

In this context, Agent-Based modeling offers a powerful paradigm for simulating and analyzing complex biological systems. By enabling the representation of individual agents, such as bacteria and molecules, and their interactions, Multi-Agent Systems (MAS) facilitate the discovery of emergent behaviors that would be difficult to predict using traditional methods. Our project builds upon an existing MAS-based Repast4py program designed to simulate biological processes related to Parkinson’s disease. This model, already incorporating the gut-brain environment, provides a foundation for exploring the influences of sugar and microbiota on the brain.

We enhance the existing simulation by incorporating a detailed and extensible representation of bacterial population dynamics in the gut. This extension aims to model the corresponding effects of gut microbiota changes on brain neurotransmitters, offering the possibility of inferring a definition of balanced diet and, in particular, of a balanced sugar intake.

Biological Background

Gut-Brain Axis

The Gut-Brain axis is a bidirectional communication system that links the gut and the central nervous system (CNS). It plays a critical role in coordinating gut and brain functions and encompasses multiple pathways, including neural, hormonal, and immune signaling. A key aspect of this system is the gut microbiota’s ability to influence brain development and function through the release of various chemicals. This influence can happen through two main communication channels: the vagus nerve and the circulatory system.

Enteric Nervous System: The gut is lined with a complex structure known as the enteric nervous system (ENS), which contains approximately 500 million neurons, earning it the nickname “second brain.” The ENS works in close connection with the CNS, with the vagus nerve acting as a primary bidirectional communication pathway, transmitting signals between the gut and the brain. Those signals coming from the ENS can alter the activity of neurons involved in the production of neurotransmitters, influencing processes such as stress response, mood regulation, and cognitive function.

Epithelial Barrier: The intestinal epithelial barrier is a selectively permeable physical barrier that allows the passage of nutrients and water while blocking toxins, pathogens, and other harmful substances. However, various factors, such as an inadequate diet or inflammation, can compromise its integrity, leading to increased intestinal permeability, commonly referred to as “leaky gut.” This increased permeability is associated with the release of larger molecules into the bloodstream, along with bacterial activity byproducts known as metabolites.

Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB): The blood-brain barrier (BBB) is a highly selective barrier that safeguards the brain from potentially harmful substances in the bloodstream. This barrier permits the passage of essential molecules such as glucose and oxygen while blocking toxins, microorganisms, and many large molecules, thereby maintaining a controlled environment for brain function. The integrity of the BBB is crucial in determining the extent to which metabolites originating from the gut can cross into the brain, potentially influencing neuroinflammatory or neurological conditions.

Microbiota and Bacteria

The intestinal microbiota consists of a diverse community of micro-organisms, primarily bacteria, that form the gut flora. Alterations in the composition of this microbial community, a condition known as dysbiosis, can disrupt intestinal homeostasis and negatively impact overall health. In fact, the microbiota contributes to critical functions such as digestion, strengthening the immune system, and protecting against pathogens, thereby promoting overall health and well-being.

Bacteria: Bacteria are microscopic living organisms that, within the human body, primarily exist as part of organized communities like the microbiota, adapting to various environments such as the gut, skin, and mucosal surfaces. Their life cycle is rapid, with reproduction occurring through a process called binary fission. During this process, a bacterium divides into two genetically identical cells, completing the cycle in just minutes or hours, depending on environmental conditions.

Each bacterium has specific nutritional requirements based on its metabolic capabilities: some consume simple sugars like glucose and fructose, which are quickly metabolized for energy, while others break down complex carbohydrates and fibers using enzymes they produce, generating beneficial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids, which are valuable to the host organism [4].

Bacteria live in colonies where they can either cooperate or compete. In cooperative scenarios, they exchange nutrients, share resources, and form protective structures like biofilms, which provide increased resistance to adverse conditions. Conversely, during competition, they may produce toxic substances such as bacteriocins to eliminate rival bacteria and more effectively colonize their environment [3].

Despite their apparent complexity, bacteria do not employ long-term strategies or possess memory. Their actions are driven by immediate responses to environmental stimuli, dynamically adjusting their metabolism and behavior based on the conditions they encounter. [5]

Influence of Sugars on the Brain

Sugars affect brain function primarily through their impact on the gut microbiota. This interaction stimulates the production of numerous biologically active substances, including metabolites and neurotransmitters, which play a crucial role in facilitating communication between the gut and the brain.

Neurotransmitters: Neurotransmitters are essential chemical molecules that enable communication between neurons within the nervous system. They are released by neurons into the synapse, where they bind to specific receptors on the membrane of the adjacent neuron, facilitating signal transmission.

The role of neurotransmitters is pivotal in regulating numerous biological processes, including movement, mood, sleep, appetite, and cognition. Interestingly, gut bacteria are also capable of producing neurotransmitters, which primarily operate within the Enteric Nervous System (ENS). Once synthesized, these gut-derived neurotransmitters can send signals to the brain via the vagus nerve, potentially prompting the brain to adjust its own production of corresponding neurotransmitters [1].

The significance of this connection is underscored by evidence that imbalances in neurotransmitter production in the brain can have profound effects, as summarized in the following table. We use these notions to better interpret our results in the result section.

| Neurotransmitter | Function | Excess | Deficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine | Used by the reward system, increases motivation and improves mood. | Associated with psychosis and schizophrenia. | Associated with Parkinson’s disease, depression, and a lack of motivation. |

| Serotonin | Improves mood, increases appetite, and reduces anxiety. | Associated with serotonin syndrome. | Associated with depression, anxiety, and irritability. |

| Norepinephrine | Increases arousal, enhances attention, amplifies stress. | Linked to anxiety, hypervigilance, and stress. | Associated with tiredness and difficulty concentrating. |

Metabolites: Metabolites play a crucial role in maintaining cerebral homeostasis and regulating the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB). These metabolites can be broadly categorized into two main groups: metabolic precursors and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs).

Metabolic precursors, once absorbed into the bloodstream, serve as raw materials for brain neurons, which utilize them to synthesize essential neurotransmitters. Among these precursors are vital amino acids, such as tryptophan, which are indispensable for brain

metabolism.

SCFAs, on the other hand, are metabolites produced by the gut microbiota through the fermentation of dietary sugars and fibers. These compounds not only serve as nutrients for bacterial populations themselves but also play a key role in regulating BBB permeability. An imbalance in the production or utilization of SCFAs can have significant consequences. For instance, if a dominant bacterial population consumes the majority of available SCFAs, other bacterial populations may be deprived of these nutrients. This can lead to shifts in the microbiota composition, adversely affecting BBB regulation. Conversely, excessive SCFA production can make the BBB overly impermeable, hindering the passage of essential metabolic precursors, such as nutrients required for neurotransmitter synthesis. [2]

This highlights the importance of a dynamic balance between bacterial populations and their metabolic products and provides a useful point of reference for the definition of a well-balanced diet that ensures an appropriate intake of sugars, complex carbohydrates, and fibers.

Model and Formalization

Structure of the Gut System

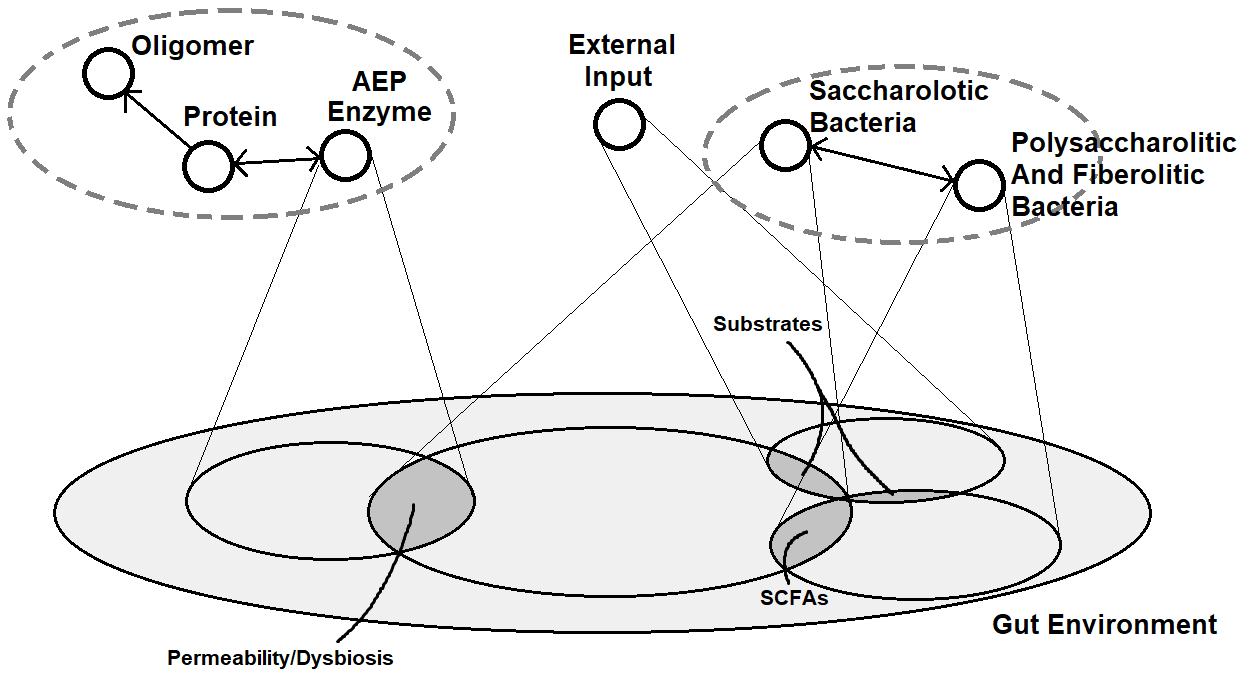

We briefly discuss the role of the Microbiota with regard to the whole system. We consider the Microbiota as a context included in the Gut environment. This is because the dynamics and interactions between agents in the Microbiota can be easily confined, so relationships between Microbiota agents (bacteria) and the remaining gut agents appear to be loosely coupled.

As schematized in the figure below, the main connection between the Microbiota and the rest of the Gut, is the overlapping of the sphere of influence of Saccharolytic (pathogenic) bacteria with the one of the AEP Enzyme. In fact, since families of Saccharolytic bacteria can directly increase inflammation, and hence negatively influencing the impermeability of the barrier, those bacteria can change the values of enviromental variables regarding the level of dysbiosis and permeability, triggering the AEPHyperactivation. If we model the Dietary Treatment as an agent, its sphere of influence overlaps with those of both saccharolytic and polysaccharolitic/fiberolitic bacteria, because of the introduction of substrates of sugars, carbohydrates and fibers, which influences bacteria population proliferation and activity.

Gut Environment

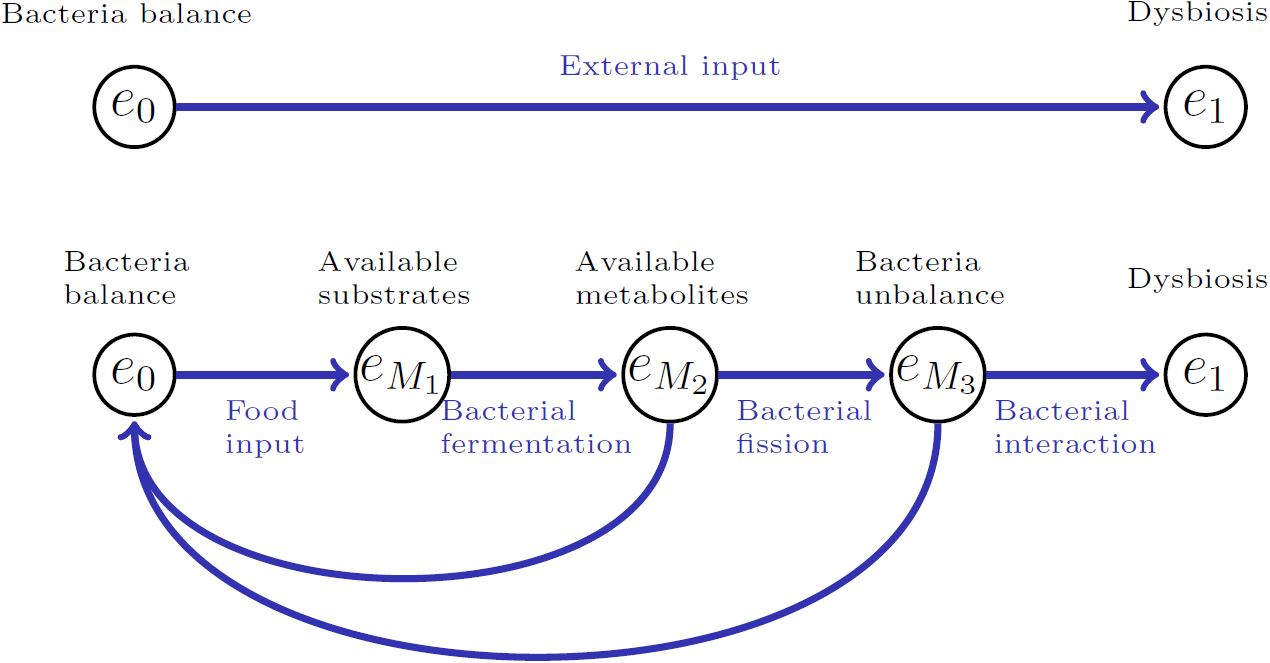

The high level model of the gut environment is enriched with additional states mediating the process leading from an healthy bacterial state to dysbiosis, i.e. an imbalance in the gut micro-biota. Hence, our formalization of the gut environment describing the emerging behavior of the system is the following:

Where:

is the set of environmental states of the Gut environment. is the set of environmental states of the microbiota context. is the state transformer function.

Gut Environment States

The semantics associated with each state in

: Balance between populations of bacteria. : State of dysbiosis, inflammation, and permeability. : AEP enzymes are in a state of hyperactivity. : Many toxic α-synuclein and τ-proteins. : Many non-phagocytosed oligomers. : Barrier reinforced. : Permeability increased.

The semantics associated with each state in the new sub-contextual environmental state space EMIC is:

: Balance between populations of bacteria. : Availability of substrates. : Availability of metabolites. : Unbalance between the population of bacteria.

Two different states for each description of the microbiota are defined to differentiate their location in the overall evolution of the gut states. For instance, while

We define the transition function τ as a mapping that associates the current state of the environment with a set of possible subsequent states, based on specific events or actions.

As the automation in the figure below illustrates, the original environment has been enriched with additional states and interactions mediating the transition from the state of balance to the one of dysbiosis. However, from the definition of τ , an analoguos automation could be drawn in order to represent the new processes of treatment, going thorough microbiotal transformation and either ending in state

Bacterium Agent

Internal state: we define the set of internal states of the bacterium agent as a set of elements representing its energy level:

Note that in order to simplify the following definitions, we make implicit use of a function lv : I → N and its inverse, representing a bijective mapping between the set of internal states and the set of natural numbers and preserving the typical order relationship, so that

Environment: in order to properly define the bacterium Agent, a more precise low-level definition of the gut microbiota environment is proposed.

Let P be the set of possible positions in the environment, S the set of substrates, A the set of SCFAs, B the set of bacteria agents, we define the gut microbiota environment as:

Note that in our current model we have

Perceptions: bacteria do have perceptions based on two main sensors: quorum sensing and nutrients sensing. While the first is used to detect the presence of other nearby bacteria, the second is used to detect nearby substances of interest like substrates and SCFAs. From these assumptions and the previous definition of

where:

is the set of states where there is at least a substrate of interest for around . is the set of states where there is at least a SCFA of interest for around . is the set of states where no substrate or SCFA of interest for is around and there is an overpopulation of bacteria around .

Actions: we consider the bacterium actions as:

where:

: is the process by which a bacterium divides into two daughter cells through binary fission. Results in population growth. : is the conversion of available substrates (e.g., carbohydrates, sugars, or fibers) into energy and metabolites such as SCFAs. : is the direct uptake of SCFAs from the environment to generate energy or sustain metabolic activities. : is the production and release of antimicrobial compounds to kill competing bacteria. : represents the action in which the bacterium is not performing any active process.

Action function: the function

In words, the bacterium behaves according to the following deterministic choices of action:

- The bacterium performs binary fission if it is at maximum energy and perceives the presence of substrates or SCFAs, as these are required to sustain the energy demands of reproduction.

- The bacterium ferments substrates if it is not at maximum energy and perceives the presence of substrates. This action allows it to replenish energy by producing SCFAs.

- The bacterium directly consumes SCFAs if it is not at maximum energy and perceives SCFAs in the environment. This provides an energy boost with minimal expenditure.

- The bacterium produces bacteriocins if it has a high or very high energy level and perceives overpopulation (indicating potential competition for resources).

- If none of the above conditions are met, the bacterium awaits better conditions.

So, as can be seen from the definition, bacteria deterministically decide their next action considering environmental and internal factors strictly related to the current moment. So, even if bacteria do have an internal state, they cannot still be considered agents having long-term strategies or goals. This is coherent with typical observed bacterial behavior.

Next function: the function

The next function is typical of adaptive agents and determines the resulting internal state of the agent after a certain action is performed. Since the set of internal states I represents the energy level of the bacterium, the definition of this function implicitly determines the cost in energy of each action.

Do function: let

Agent Definition: a bacterium can be defined as an adaptive agent as follows

Where:

Bacteria Families

Note that as bacterial families can vary considerably in terms of actions they can perform and perceptions, this formalization provides a base version of the bacterium agent that has been extended in the implementation, for instance, taking into consideration bacteria that are able to move or can ferment precursors into neurotransmitters. The table below shows the eight bacteria families that have been included in the final model ordered by the fermented substrates: Simple Sugars (SS), Complex Carbohydrates (CC) and Fibers (F). The presented peculiar characteristics of each family have been derived from realworld observations and studies, sometimes recurring to adaptations and simplifications.

| Family | Ferments | Produced Precursors | Produced SCFAs | Also Consumes | Produced Neurotransmitters | Moves | Produces Bacteriocins |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enterobacteriaceae | SS | Tryptophan, Tyrosine | Acetate | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Clostridiaceae | SS | - | Butyrate, Acetate | - | Dopamine, Serotonin, Norepinephrine | - | - |

| Lactobacillaceae | SS | - | Acetate | Propinate | Serotonin, Norepinephrine | ✓ | ✓ |

| Streptococcaceae | SS | - | Acetate | - | - | - | ✓ |

| Ruminococcaceae | CC, F | Tryptophan, Tyrosine | Butyrate, Acetate | Propionate | - | - | - |

| Lachnospiraceae | CC, F | - | Butyrate, Propionate | Acetate | - | - | - |

| Prevotellaceae | CC | - | Propionate | Acetate | - | - | - |

| Bifidobacteriaceae | CC | Tryptophan | Acetate | Butyrate | Serotonin | ✓ | - |

Implementation

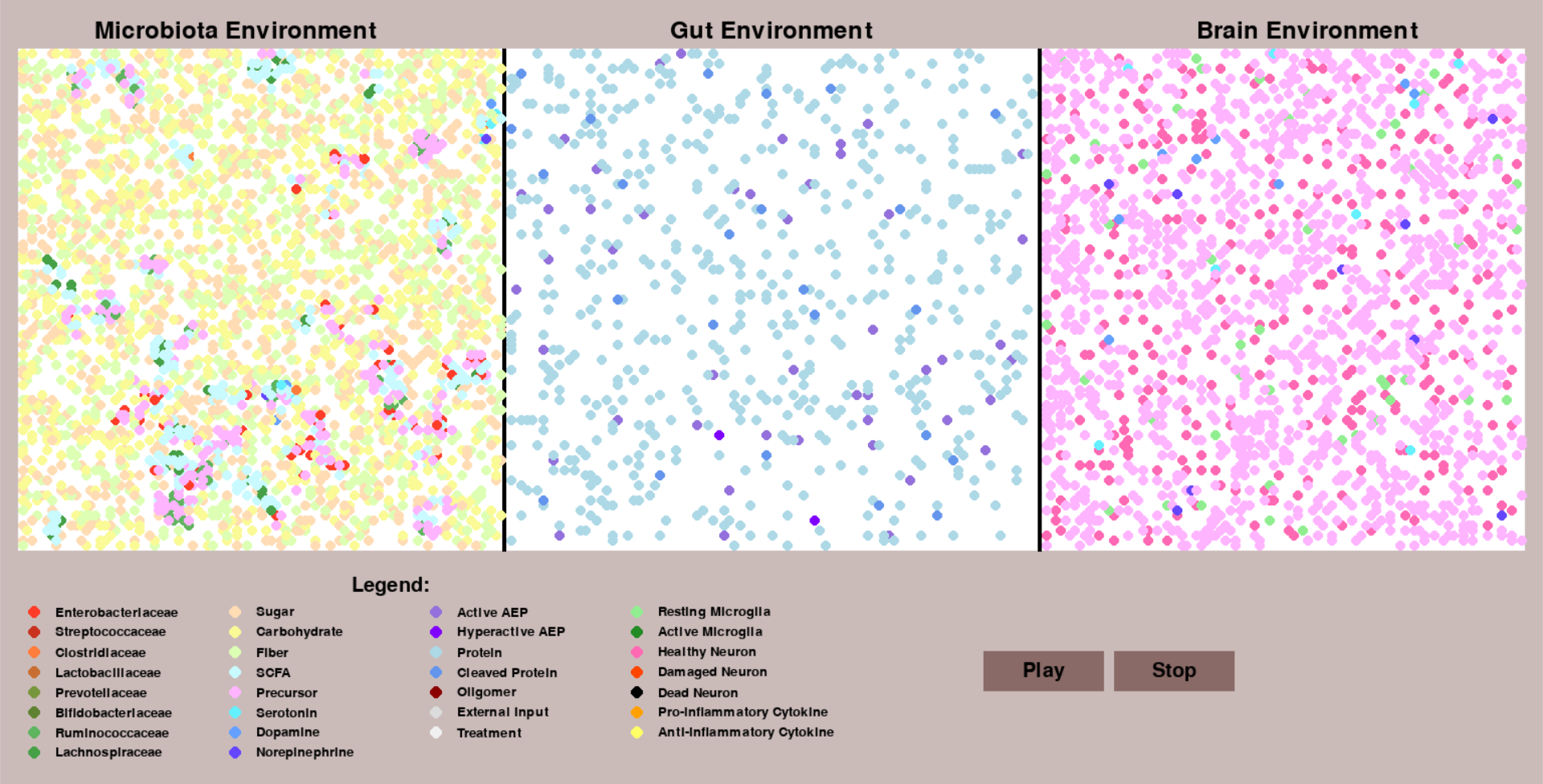

The base python code utilizing the Repast4Py library has been enriched with extra features, centered around the Microbiota, to illustrate the newly introduced behaviors in the system. The original code of the project has been refactored to render better and cleaner code structure. The user interface, based on the Pygame library, has also been extended to allow for the visualization the new microbiota environment. As can be seen from the screenshot below, the view Microbiota has been included, showing a subset of the agents in this context, which is also customizable.

Bacteria were redefined from being simple numerical values to proper adaptive agents which are able to interact with and influence the environment around them. Several families of bacteria were introduced to observe an extensive variety of behaviors that can come into play.

For bacteria to thrive they require resources. To ensure a satisfactory level of environment dynamics these too were introduced as agents - more like entities than full blown agents as they only passively exist.

Microbiota

The Microbiota is responsible for the coordination of the Bacterium agents contained within it, as well as the handling of its resources. It essentially takes care of the evolution of the ecosystem across steps. At the execution of each step of the simulation it synchronizes actions with the consequences thereof. When the environment executes a step, consumed resource agents are discarded and new agents, be it resource or bacteria, are also created as required.

Bacteria has to carry out specific actions to obtain specific outcomes, but some of these actions require the direct intervention of the Microbiota environment to take effect. Actions like fission and consumption, which require the creation and destruction of other agents, are beyond the scope of influence of any agent to take full effect and requires instead the involvement of the environment. In other words, the do function of the bacterium agent is implemented by the Microbiota class. The bacteria communicates its intended action to the Microbiota by setting state variables that indicate the determined action.

def _fission(self , bacterium): """ Applies fission to a bacterium agent, creating a new bacterium agent in an empty position around the bacterium. If no empty position is found, the fission is not applied, but the state of the bacterium remains unchanged in order to try again in the next step. :param bacterium: The bacterium agent to apply fission """ empty_ngh_pts = self.find_bact_free_nghs(bacterium.pt) if len(empty_ngh_pts) == 0: return point = Simulation.model.rng.choice(empty_ngh_pts) bact_class = type(bacterium) new_bacterium = bact_class(Simulation.model.new_id(), Simulation.model.rank, dpt(point[0], point[1]), self.NAME) self.context.add(new_bacterium) bacterium.toFission = False

def step(self): removed_ids = set() self.context.synchronize(restore_agent) self.remove_agents(removed_ids) self.add_substrates() self.make_agents_steps() self.add_bacteria() resources_to_move = [] for agent in self.context.agents(): if isinstance(agent , ResourceAgent) and agent.toMove: resources_to_move.append(agent) agent.toRemove = True self.move_resources_to_brain(resources_to_move) self.remove_agents(removed_ids) self.apply_actions() self.remove_agents(removed_ids) self.count_bacteria() self.context.synchronize(restore_agent) self.remove_agents(removed_ids)

Bacterium

The Bacterium class is a base class from which all bacteria families inherit. It describes common attributes and behaviors shared by bacteria. During the execution of a bacteria step in the simulation they can both observe their immediate surroundings and perform an action. Performing an action comes at a certain energy cost, therefore, the energy of bacteria is also updated after they execute an action.

def step(self) -> None: """ This function describes the default behaviour of the bacteria agent in the environment. """ per = self.percept() self.perform_action(*per)

However, the outcome of same behaviors, as well as their nature, varies between families - some bacteria can cause inflammation while others do not. For example, they can ferment different substrates and precursors, or none at all. Systems are put in place to ensure that bacteria can only perform actions which are expected of the family in which they belong.

Resources

Resources are any agents that can be consumed or used by other agents during the simulation. There are different kinds of resources present in the system, each described by their own specialized class which extends the base ResourceAgent class. Neurotransmitters are one of such resources. When situated in the brain they are used as a means of communication by neurons, while in the Enteric Nervous System they are used to signal to the brain to create their equivalents within itself. Bacteria on the other hand consume resources such as Substrates and Short-Chain Fatty Acids to either produce other resources or to sustain themselves. Resources can be transported from the gut environment and Microbiota to the brain via the bloodstream interface, but not every resource from the bloodstream is allowed into the brain - the blood-brain barrier makes sure of this. However, certain conditions must be met for the successful transportation of a resource out of the gut environment.

def check_if_to_move(self , permeability_check: bool = True): """ Checks if the agent should move from its current environment to the brain through the bloodstream. """ if self.pt is None: return nghs_coords = Simulation.model.ngh_finder.find(self.pt.x, self.pt.y) if self.context in {’gut’, ’microbiota’}: choice = Simulation.model.rng.integers(0, Simulation.params["epithelial_barrier"]["min_impermeability"] if permeability_check else 100) if choice > Simulation.model.epithelial_barrier_impermeability: self.toMove = True

Neuron

The already existing neuron agent has been updated according to the introduced improvements. In particular, the introduction of new resources have led to the need for the neuron to be able to perceive precursors and produce neurotransmitters. As can be seen in the code snippet below, the neuron saves as an internal state the availability of neurotransmitters and the rate at which it produces them. Availability of neurotransmitters strictly depends on the availability of precursors in its neighborhood, which can be perceived and absorbed. On the other hand, the rate at which the neuron produces neurotransmitters depends on the influence of the vagus nerve and the neuron’s state, and for this reason is externally managed by the GutBrainInterface class.

Availability of neurotransmitters decreases as the neuron produces them, and the rate at which the neuron produces neurotransmitters also decreases over time if no stimuli are received from the vagus nerve. This allows us to model and observe possible imbalances and spikes in neurotransmitter production, which in our model are fundamentally related to the evolution of the microbiota.

def produced_neurotransmitters(self) -> Dict[NeurotransmitterType, int]: """ Returns the neurotransmitters the neuron is able to produce in the current step. :return: Dict with neurotransmitter type as key and the amount of neurotransmitter as value """ return {neurotransmitter: min(self.neurotrans_availability[neurotransmitter], self.neurotrans_rate[neurotransmitter]) for neurotransmitter in NeurotransmitterType}

def change_neurotransmitters_to_produce(self): """ Changes the neurotransmitters the neuron will produce in the next step. The neuron can increase the availability of a neurotransmitter if it has a precursor in its neighborhood, otherwise it can decrease the availability depending on the neuron’s state. The rate at which the neuron produces neurotransmitters is also changed towards the minimum, which is 1 per neurotransmitter. """ for neurotransmitter in self.neurotrans_availability: if self.state == NeuronState.DEAD: self.neurotrans_availability[neurotransmitter] = 0 else: self.neurotrans_availability[neurotransmitter] = max(0, self.neurotrans_availability[neurotransmitter] - Simulation.params["neurotrans_decrease"][self.state.name] * self.neurotrans_rate[neurotransmitter]) precursor = self.percept_precursor() if precursor is not None: neurotrans = np.random.choice(precursor.precursor_type.associated_neurotransmitters()) self.neurotrans_availability[neurotrans] += Simulation.params["precursor_boost"] precursor.toRemove = True for neurotransmitter in self.neurotrans_rate: self.neurotrans_rate[neurotransmitter] = max(1, self.neurotrans_rate[neurotransmitter] - 1)

Results

In this section we analyze preliminary results obtained from the implemented model. In order to evaluate the potentiality of the system in determining a possible definition of balanced diet, the simulation was run with different configurations regarding the various substrates intakes, while maintaining fixed all the other parameters.

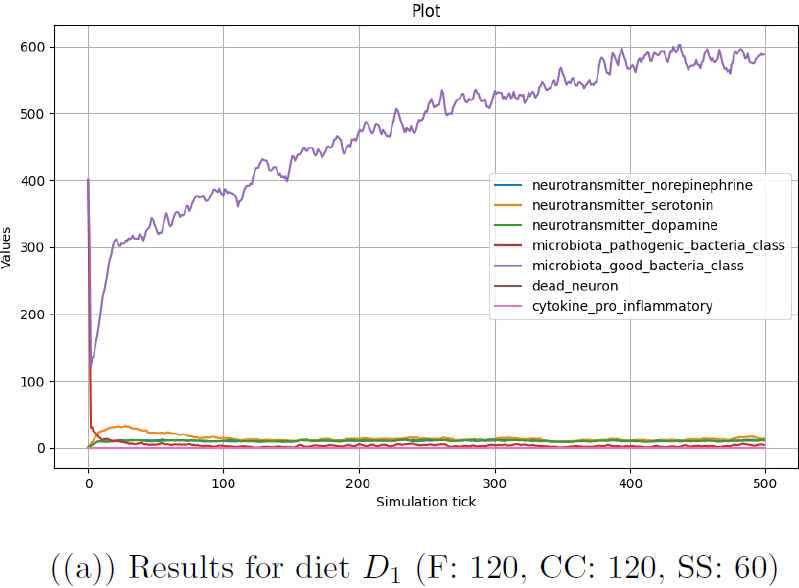

We chose three different configurations of substrates, each of them corresponding to a different dietary regime. These are defined by the relative amounts of fibers (F), complex carbohydrates (CC), and simple sugars (SS). In the following descriptions, F, CC, and SS will represent the initial number of resource agents of type fiber, complex carbohydrate, and simple sugar, respectively.

The three tested regimes are the following:

The remaining parameters were kept as follows:

- All eight bacteria families were present in the microbiota, with 100 bacteria of each

family. - No ExternalInput or Treatment agent was present.

- Bacteria actions costs were set as in the presented

- The other relevant parameters were set as in the table below.

seed : 42 world . width : 100 world . height : 100 microbiota_diversity_threshold : 100 substrate_max_age : 10 epithelial_barrier : { initial_impermeability : 80, min_impermeability : 30, permeability_threshold : 25, } blood_brain_barrier : { initial_impermeability : 50, minimum_impermeability : 1, maximum_impermeability : 99, scfa_permeability_influence : 1 } neurotrans_max_age : 8 neurotrans_reuptake_percentage : 50 neurotrans_initial_availability : 5 precursor_boost : 10 neurotrans_rate_increase : 3 neurotrans_decrease : { HEALTHY : 1, DAMAGED : 3 } aep_enzyme . count : 50 tau_proteins . count : 300 alpha_syn_proteins . count : 300 tau_oligomers_gut . count : 0 alpha_syn_oligomers_gut . count : 0 active_microglia . count : 0 resting_microglia . count : 50 neuron_healthy . count : 300 neuron_damaged . count : 0 neuron_dead . count : 0 cytokine . count : 0 alpha_syn_cleaved_brain . count : 0 alpha_syn_oligomer_brain . count : 0 tau_cleaved_brain . count : 0 tau_oligomer_brain . count : 0

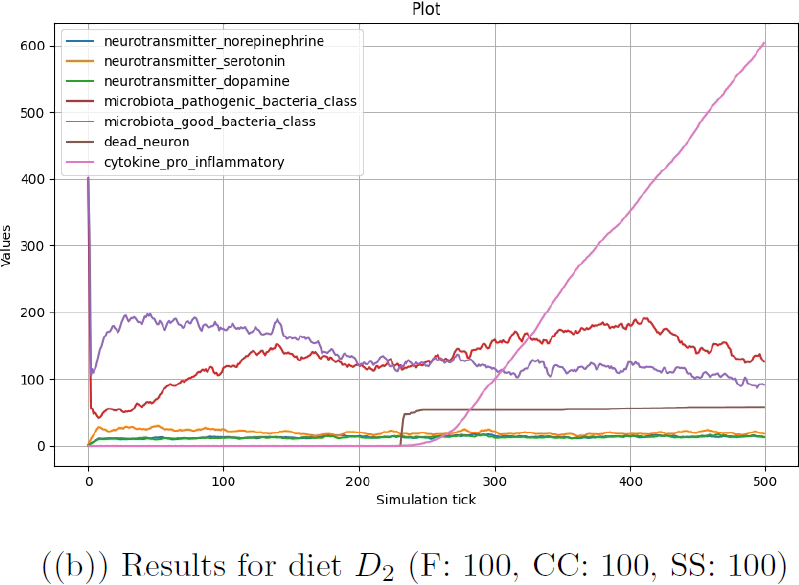

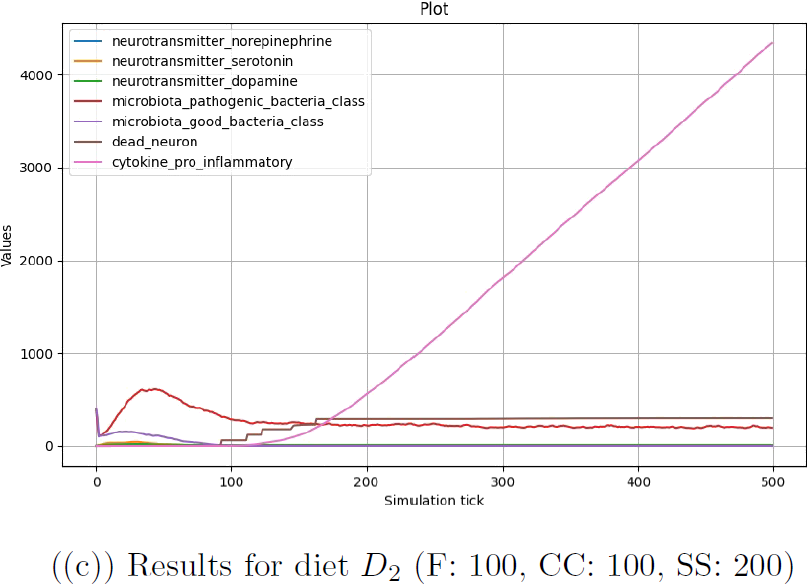

Each of the three configurations was run for 500 step for 5 times, and the results were averaged for each configuration and each step. In Figure 4.1, results are plotted for the number of good and pathogenic bacteria in the microbiota and the number of each type of neurotransmitter in the brain. The number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and dead neurons in the brain is also included to evaluate the relationship with the already existing part of the model.

Figure (a) represents the evolution of the system in the case of diet

The number of pro-inflammatory cytokines and dead neurons also remains zero, as the microbiota remains in a healthy state and the conditions for immune response trigger are never met.

Figure (b) illustrates how the system generally evolved in the case of diet

Finally, Figure 4.1(c) represents the system evolving in response of diet

Conclusion

The model presented in this work represents a first attempt to enhance the existing simulation in order to reproduce the complex interactions between the microbiota and the brain, with the aim of understanding the role of the microbiota in the development of neurodegenerative diseases and provide a possible definition of a balanced diet.

The model was extended to include a more detailed representation of the microbiota, with the introduction of different bacteria families and the possibility of simulating the competition between them.

The model was also extended to include the possibility of simulating the production of neurotransmitters by neurons and the influence of the microbiota on such production.

We analyzed the evolution of the system in response to different dietary regimes, and the results showed that the model is able to capture the effects of different diets on the microbiota and the brain, coherently with the expected outcomes.

This preliminary study suggests that, according to the model, the two diets

Further analysis would be needed to discover the exact edge values of the parameters that define a balanced diet according to the model, and to understand the dynamics of the system in response to different parameters outside the diet.

References

[1] L. Dicks. Batteri intestinali e neurotrasmettitori. Microorganisms, 10, 2022.

[2] K. Bell et al. L’integrazione alimentare basata su metaboliti nel diabete di tipo 1 umano è associata al microbiota e alla modulazione immunitaria. Microbiome, 10, 2021.

[3] H. Majeed et al. Competitive interactions in escherichia coli populations: the role of bacteriocins. The ISME Journal, 5

[4] K. Oliphant, E. Allen-Vercoe. Macronutrient metabolism by the human gut microbiome. Microbiome, 7, 2019.

[5] S. Kitamoto et al. Microbial adaptation to the healthy and inflamed gut environments. Gut Microbes, 12(1), 2020.